All about Tiruppur’s transformation, the huge cost of it, and where it fits in the global push for sustainable textiles.

India holds 3.9% of the global textile and apparel trade as the world’s sixth-largest exporter. Yet the bleaching and dyeing that drive this success also poison its rivers and soils. One city illustrates this story more sharply than anywhere else: Tiruppur.

Tiruppur’s rise and fall as the Knitwear Capital

When India brought economic reforms in the 1990s, the already established textile hub of Tiruppur, a small city in Tamil Nadu, began to flourish with growing export demand. The large number of factories turned the city into the ‘it’ spot for bleaching and dyeing cotton-knit textiles. It even got the name ‘Knit-wear capital’ because of its high production and export numbers. Demand grew, production increased, and the industry expanded.

By the 2000s, Tiruppur accounted for more than 54% of India’s knit-based textile exports. But things were taking a darker turn for the farms and the river outside the factories. The colossal amount of chemicals (given the high production volume) being released into the Noyyal river had a devastating effect—tonnes of dead fish, and once-blooming fields of plantain, paddy, and turmeric lay barren.

How Pollution and Court Orders Brought the Industry to a Halt

The Pollution Control Board, which began functioning in the city in the early 1990s, had issued guidance for factories at various times. It first asked the industry to remove colours before releasing wastewater into the river, then to store wastewater on their own land instead of releasing it (which had destroyed land and groundwater), and later to implement zero-discharge policies. However, the disparate guidance, incomplete understanding of the chemicals involved, and lack of enforcement left Tiruppur in a dire predicament.

In 2011, the Madras High Court ordered a complete shutdown of the industry. Over 700 bleaching and dyeing units, as well as common effluent plants, were closed. More than 50,000 workers lost their jobs, and the city suffered losses of about ₹50 crore per day. The Court’s requirement was clear: only after installing a zero-discharge system to prevent environmental harm could the industry resume operations.

Tiruppur’s Zero Liquid Discharge (ZLD) Journey

After a slow, steady, and pain—and money—staking process, Tiruppur is now hailed as a sustainable textile hub. Today, there are over 360 dyeing units operating in and around Tiruppur. Of these, around 50 have their own Individual Effluent Treatment Plants (IETPs), while most participate in 18 Common Effluent Treatment Plants (CETPs) for wastewater treatment.

While it’s difficult to pinpoint the exact investment in Tiruppur’s transformation, the industry itself invested over ₹1,013 crore in establishing ZLD enabled CETPs, in addition to the government support of more than ₹200 crore. The investment seems to have fared well, since today, reports estimate the industry’s overall trade turnover at ₹70,000 crore.

How the Tiruppur ZLD System Works

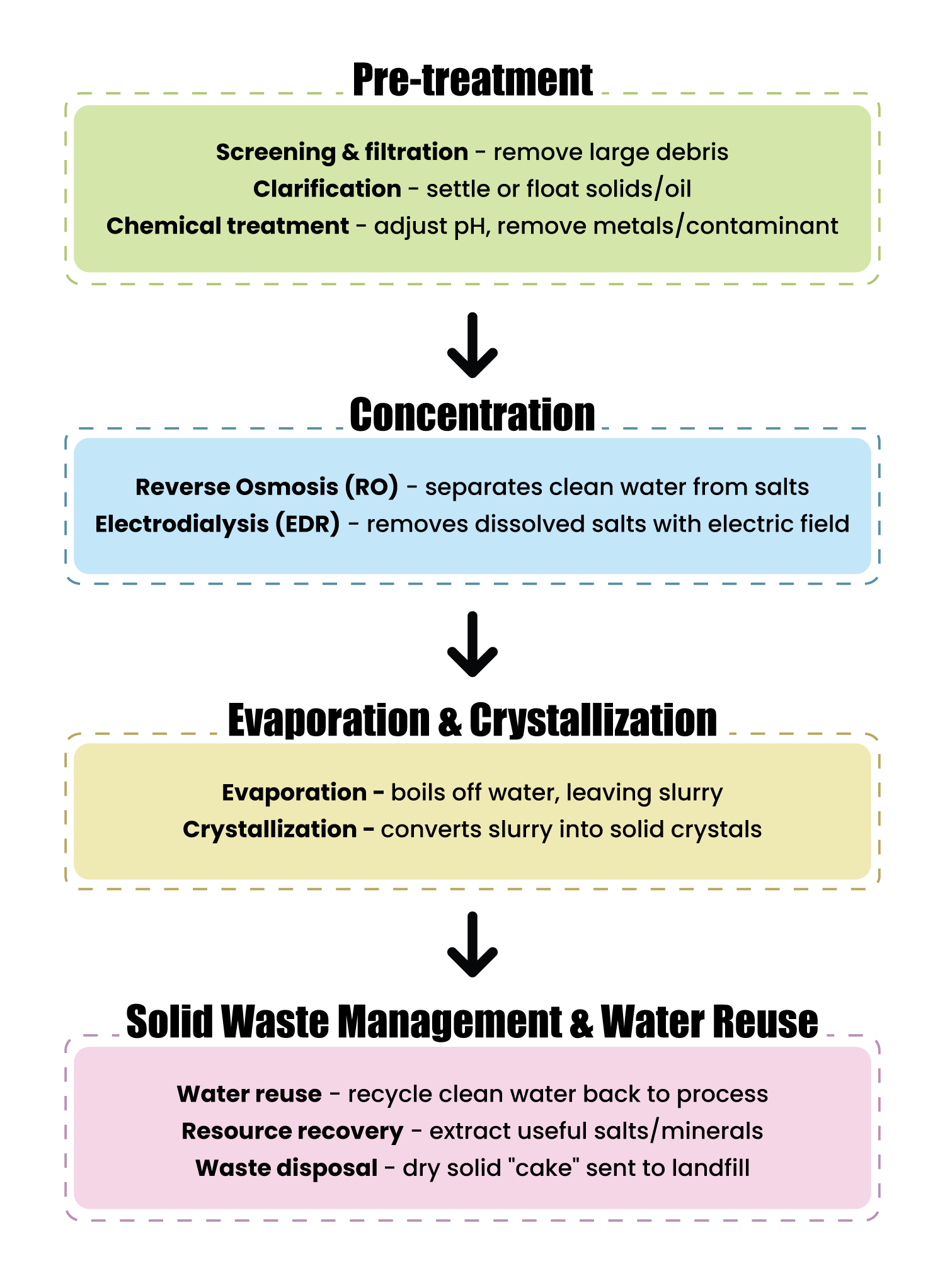

After numerous experiments and failures, the industry realised that neither filtering out colours nor storing partially filtered, chemically laden water was effective in protecting the environment. After huge amounts spent in research and development, trials, errors, and improvements, machines were deployed for the ZLD process.

The ZLD process looks comprehensive. It ensures that no waste goes unchecked, maximizes water recycling and reuse, reduces the need for freshwater, and ensures the environment is not harmed. Sudhakaran Kalidas, Joint Secretary of the Dyers Association of Tiruppur, told The Economic Times:

“The amount of water the Tiruppur cluster recycled every day is equivalent to 50% of the total drinking water consumed by people in Tamil Nadu.”

Reports indicate that CETPs and IETPs in Tiruppur treat 130 million litres of dye effluent daily and recover 92% of pure water for reuse in the processing process.

In addition to water recycling, the industry is now also recycling plastics, fibre, cardboard boxes, and more.

The Cost of Sustainability, and Can India Afford it?

All this, and the industry’s return to a flourishing stage, may seem like a complete story, ready to inspire the rest of India. And while Tiruppur and India might have won a battle, the war is far from over.

A major challenge in reviving the industry has been the high costs of installing and operating ZLD machinery. Setting up a typical ZLD plant in India costs between ₹40 lakh and over ₹5 crore, especially for large units. Energy-intensive processes like evaporation and crystallisation add to these expenses. In Tiruppur, the 18 CETPs consume 10 million units of electricity each month, at a cost of ₹30 crore.

Since Tiruppur had big industrialists with capital and government support, the change was possible. Perhaps the same industrial base and government could work to expand green energy capacity (from the current 1,950 MW) to meet these energy needs.

But can we really expect small dyeing clusters, which account for over 40% of India’s textile production, to adopt these systems? If not, will we keep ignoring them, letting pollution destroy water bodies and farmland until disaster strikes, as it did in Tiruppur? Even though Tiruppur has changed, dyeing and washing factories in other towns still pollute the Noyyal River. Meanwhile, the Yamuna River still awaits rejuvenation programs after receiving years of untreated waste from textile, dyeing, and bleaching units.