What should be the top priority for a country that’s one of the world’s largest contributors to plastic pollution? Build a system that doesn’t let plastic harm the environment or its people. That would make sense, right?

So, in line with several European countries, India introduced Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) norms, a policy where the burden of plastic recycling falls on the producer (the one who benefits from using plastic in production), not the local authorities. Under EPR, manufacturers are required to meet annual recycling targets that correspond to the volume of plastic they produce.

But how do companies comply? For plastic packaging, common in food, cosmetics, and FMCG products, businesses typically follow one of three routes:

- Recycle the mandated quantity of plastic themselves

- Outsource the task to a PRO (Producer Responsibility Organisation)

- Or buy EPR credits from PROs who recycle plastic independently

In theory, this looks like a working system, but like many others, it is a leaky and poorly regulated model.

The Loopholes in India’s Plastic Recycling and EPR Policy

In 2022, India generated an estimated 10 million tonnes of plastic waste. According to the India Plastics Pact 2023 report, the country had around 2,309 plastic recycling units, with a combined capacity of just 4.77 million tonnes per year. That’s a glaring gap between production and management.

Even if capacity has improved in the last three years, many of these recycling units — much like those in e-waste management — are either non-operational, fake, or of substandard quality. For example, a Newslaundry investigation found that 31 out of 41 e-waste plants across four states were either non-existent or running ghost operations. Similarly, IPP reported that 25% of plastic recycling units were fake, shut down, or didn’t exist.

Experts have long flagged issues like:

- Fake recycling certifications

- Fake PROs selling real EPR credits

- The exclusion of India’s vast informal recycling sector, which handles over 90% of the country’s plastic waste

Yet, nothing changes.

Who’s watching the recyclers?

The situation is made worse by weak quality control at existing recycling units. A 2023 CPCB audit found over 600,000 fake plastic recycling certificates issued by companies in Gujarat, Maharashtra, and Karnataka. So, instead of helping producers responsibly manage their plastic, many recycling units are helping them dodge accountability.

And they’re getting away with it because regulators don’t seem to be regulating. The CPCB conducts occasional audits but rarely updates or shares data on the condition of recycling units. Its website lists registered stakeholders, but this information isn’t publicly accessible. For most citizens, tracking real recyclers remains difficult.

And what of the PROs on that list? We already know many of them are ghost operations, as revealed by multiple reports.

No checks, no standards, and workers at risk

Amidst all of this, perhaps the most shocking aspect is the fact that there is no CPCB report or audit to verify whether registered recycling plants, if they exist at all, adhere to safe and standard recycling practices.

Simultaneously, India’s waste collection system is already largely informal, with a reported 80% of waste collection being informal, and an estimated 10,000+ waste pickers per city working in unsafe conditions without gloves or masks. These workers sort through hazardous waste, while recycling units, which also pose major health risks, continue to operate unchecked. The system, therefore, not only poses environmental risks but also potentially breaches several human rights.

A broken funnel: what gets collected still ends up polluting

However, the problem isn’t just limited to recycling plants; even if plastic is collected, whether by formal agencies or informal workers, 30% of it ends up in uncontrolled landfills, leaching toxins into the soil and water, which can then reach our crops. The rest is often too contaminated to recycle or never reaches functioning plants at all.

The biggest contributor to this mess in our country, the plastic packaging industry, is currently valued at over USD 22 billion and is expected to grow to USD 26 billion. Without a waste management system that matches this growth, we will only see more plastic being dumped in our rivers, landfills, and oceans.

So, what good is a policy if it isn’t enforced?

The rules aren’t even clear to the plastic industry

But is the policy even good enough in the first place? Interestingly, many companies have complained that the EPR policy — originally introduced in 2016 — is still poorly formulated. As late as 2020, some companies were unable to meet their targets simply because they didn’t understand the rules. For instance, pharmaceutical companies initially didn’t even realise they fell under the compliance category.

Even now, many businesses, especially smaller ones, struggle with several issues:

- Unclear documentation requirements

- Poorly designed online compliance portals

- Lack of clarity on penalties and reporting formats

Larger corporations can afford to hire consultants or build in-house compliance teams. However, small businesses often lack the necessary resources and technical expertise to navigate the system effectively. Perhaps one reason smaller businesses resort to fake certifications is simply that the policy is too complex and difficult to follow.

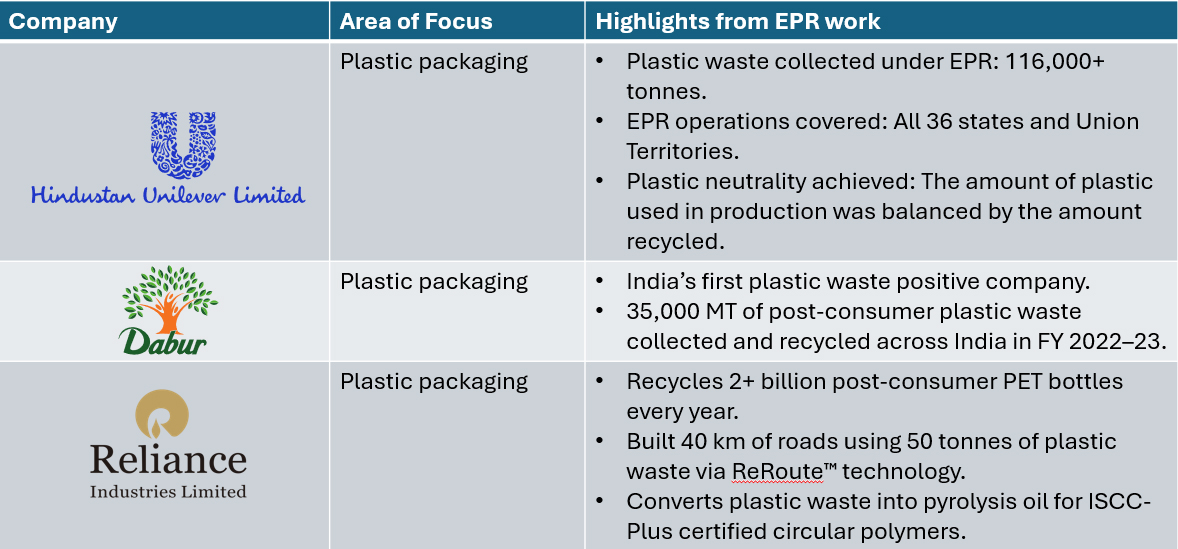

Which is why, if you look for Indian companies with the best EPR compliance record, the list is dominated entirely by the country’s largest corporations.

While the list may be impressive, it reflects only one side of the EPR story. These numbers show what EPR could achieve, but right now, only a handful of companies are actually engaging with it. This is clear from the fact that only 30% of the plastic waste generated annually is recycled in India.

Where do we go from here?

The policy supposed to tackle our country’s plastic crisis seems to be choking on its own loopholes. If India truly wants to tackle the problem, it needs to rebuild the EPR ecosystem from scratch, starting with accountability, transparency, and effective enforcement. However, the next step should be to replace plastics with alternatives wherever possible. Because the rapidly rising plastic production, expected to grow to $68.33 billion by 2030, will soon overwhelm the recycling industry and likely cause an environmental collapse.