All’s well that ends well. But does it?

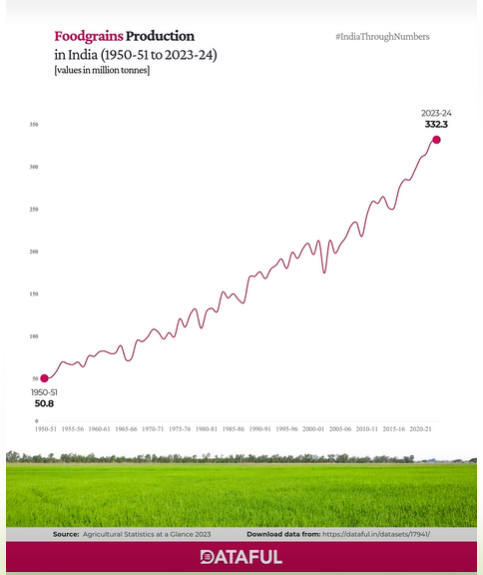

Economists, policymakers, and administrators often point to the Green Revolution as one of India’s greatest achievements since independence. It is widely credited with transforming the country from food scarcity to food security. Crop yields increased, farm incomes improved, and India emerged as a major producer and exporter of grains, fruits, and vegetables. On paper, the numbers are undeniably impressive.

But numbers rarely tell the whole story.

The Rise of Hybrid Seeds in Indian Agriculture

Most people assume that pesticides and fertilisers powered this transformation. That assumption is only partly true. The real shift came from hybrid seeds. Simply put, hybrid seeds are created by crossing two different parent plants to produce a first-generation crop that performs better than both parents. These crops typically yield more, grow uniformly, and produce more biomass. During the Green Revolution, hybrids were aggressively promoted for crops such as maize, sorghum, pearl millet, and later rice, supported by government subsidies, assured procurement, and expanded irrigation.

The problem is that the advantage of hybrid seeds lasts only one generation. Unlike traditional seeds, hybrids cannot be reliably saved and replanted. When farmers reuse seeds from a hybrid crop, yields fall sharply, and plant quality becomes uneven. Farmers are therefore forced to buy fresh seeds every season. Seed saving, a practice that provided security for centuries, gradually disappeared. As seed sovereignty slipped away, especially for small and marginal farmers, control within the agricultural system shifted from farms to seed companies.

This is where the foundational problem begins.

It is important to note that hybrid seeds did deliver on what they promised — higher output. [Refer Table 1]

| Crop Category | Hybrid/Variety | Key Outcome | Socio-economic Impact |

| Vegetables | Selvam (Okra) | Long shelf life | Reduced debt, higher market premium |

| Pulses | ICPH 2671 (Pigeonpea) | ~40 q/ha yield | Breakthrough in stagnant yields |

| Oilseeds | NARI Safflower | 45% oil content | Higher income, dye by-products |

| Cereals | Kokila-33 (Rice) | 110-day maturity | Climate resilience, higher yield |

| Fodder | CO-4 (Napier grass) | 1000+ kg/acre | Livestock security, diversification |

The Hidden Cost of the Hybrid Seed Package

So, what went wrong? The answer lies in the package. Hybrid seeds were never introduced alone. They came bundled with specific fertilisers, pesticides, irrigation schedules, and cultivation practices. In Telangana, for example, the hybrid rice seed industry evolved into a centralised, contract-based system. Seed companies captured the largest share of value, but seed growers also benefited from technical support and price assurance.

However, this success depended entirely on access — access to capital, irrigation, chemicals, and technical advice. Farmers who had these resources thrived. Those who did not were left behind. The averages looked positive, but they masked a widening divide. Small farmers struggled to afford specialised seeds, fertilisers, nitrogen, pesticides, and water. When yields fell short of expectations, debt followed.

This happened because a critical question was never clearly answered: where and when should hybrid seeds be used?

Bt Cotton and the Limits of the Hybrid Seed Model

Hybrid seeds are often presented as a universal solution. Yet their large-scale use in India has produced failures serious enough to demand reflection. The clearest example is Bt cotton.

Introduced in 2002, hybrid Bt cotton was marketed as a revolutionary answer to the American bollworm. Two decades later, it is evident that India’s Bt cotton model was deeply flawed. Unlike most cotton-producing countries that use short-duration, high-density varieties, India adopted long-duration hybrids grown at low density. Hybrid seeds were expensive, so farmers planted fewer plants. But longer crop duration meant longer exposure to pests.

Over time, the native pink bollworm developed resistance to Bt toxins. Farmers were forced back to heavy pesticide use. This chemical resurgence disrupted ecosystems and triggered outbreaks of secondary pests such as whitefly and mealybug. In states like Maharashtra, cotton yields have stagnated since 2007 despite near-universal Bt adoption. High seed costs, flat yields, and erratic monsoons trapped farmers in a cycle of rising inputs and growing debt. Furthermore, the annual need to purchase expensive seeds and chemicals, with no guarantee of returns, became a major driver of distress and farmer suicides.

So the question must be asked: Is it always right to replace traditional seeds with “advanced” hybrids at every single farm?

High Yields, High Chemical Inputs, Exhausted Soils, Polluted Environment

Hybrid seeds carry a deeper contradiction: Selectively high yield, but rising input dependence, chemical intensification, and slow soil exhaustion. Hybrids are bred to be input-responsive. In simple terms, they perform well only when fed large doses of fertilisers and protected with chemicals. Studies on hybrid rice in West Bengal show that farmers need up to 160–200 kg of nitrogen per hectare to unlock yield potential.

Simultaneously, research from Assam indicates that hybrid rice cultivation costs approximately 30% more than traditional rice cultivation. The steepest increases are in pesticides, irrigation, and seed costs. Conventional systems often require little to no chemical protection, making them cheaper and more sustainable. After all this, you’re forced to wonder if this system is designed to help farmers, or to sell more fertilisers and pesticides, quietly favouring those who can afford them?

[Read more on India’s self-sabotaging agrochemical policies here]

In many cases, the extra “care” does not even deliver proportionate gains. Across rice-growing regions, the yield advantage of hybrids over improved open-pollinated varieties is often marginal. This is one reason conventional rice varieties are returning in China: they offer competitive yields, lower input needs, and better market prices. The gap between hybrids and well-bred traditional varieties is narrowing.

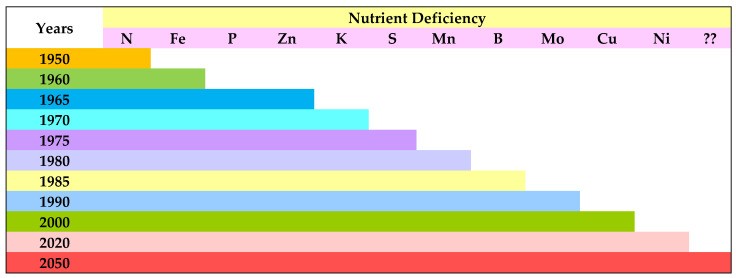

There is a reason for this shift. Continuous monocropping of hybrids strips soils of nutrients. India’s ideal nitrogen–phosphorus–potassium ratio of 4:2:1 has drifted to 5:2:1 or worse in some regions. This imbalance has depleted organic carbon and caused widespread micronutrient deficiencies, such as zinc, sulphur, iron, and boron. Soil pH has shifted, beneficial microbes have been damaged, and in states like Haryana, modern agricultural practices are linked to salinity, erosion, and waterlogging.

Water contamination followed. Excess nitrates leach into groundwater, making it unsafe for drinking and increasing health risks. Pesticide residues now appear in rivers and lakes well beyond safe limits, disrupting aquatic ecosystems and food chains.

Hybrid crops are also water-intensive, a critical issue in a country where agriculture consumes over 90% of freshwater. Subsidised irrigation for rice and sugarcane has drained groundwater in Punjab and Haryana to dangerous levels.

After soil and water came air. To prepare fields quickly for the next hybrid crop, farmers burn crop residue, releasing massive amounts of greenhouse gases and choking North India each winter. Earlier, farmers used to allow for natural decomposition when planting traditional seeds.

India’s Journey from Food Security to Nutrition Insecurity

After all this, one question remains: are hybrid crops even healthy?

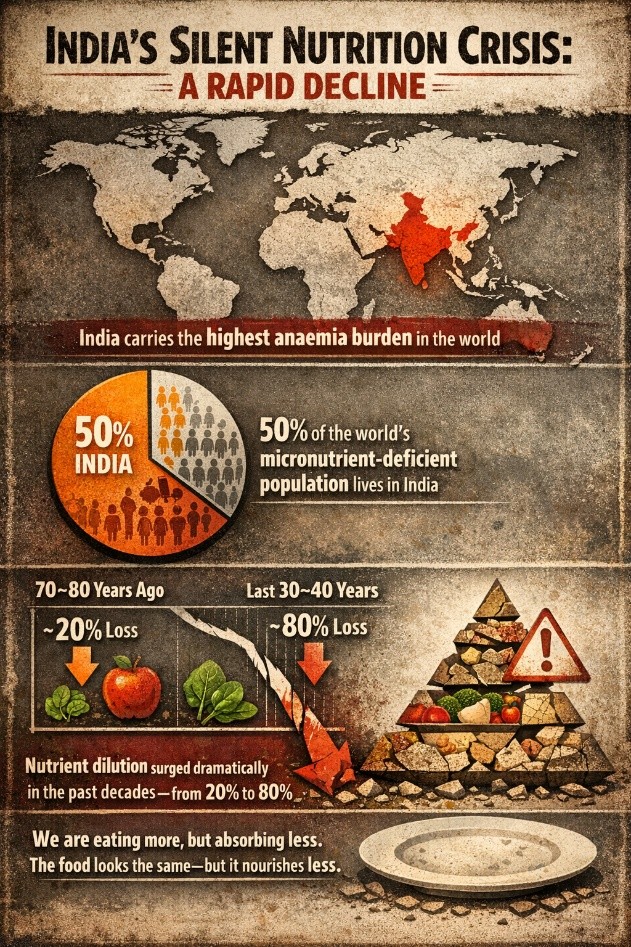

Many may accept environmental damage as collateral, as long as food reaches the plate. But what if that food is nutritionally hollow?

India was once home to over a lakh indigenous rice varieties, adapted to specific soils, climates, and medicinal needs. In just a few decades, most have vanished. Seed banks show that nearly 80% of collected landraces are no longer cultivated.

These varieties carried traits that hybrids cannot replicate, like flood tolerance, salt resistance, and high micronutrients. Millets like kodo and kutki, once staples for tribal communities, were pushed aside by wheat and cotton. They required little water, no chemicals, and were naturally resilient, yet received none of the policy backing given to hybrid cereals.

When elders say food has lost its taste, they are not romanticising the past. Hybrid crops prioritise size and shelf life, not nutrition. India may be food-sufficient, but it is increasingly nutrient-deficient.

| Nutrient | Loss Range | The “Then vs. Now” Comparison |

| Copper | 20% to 76% | At the worst end (76% loss), you’d need to eat 4 bowls of vegetables to get the copper found in 1 bowl in the 1940s. |

| Zinc | 27% to 59% | To get the same zinc, you’d need roughly 2.5 servings of food for every 1 serving your grandparents ate. |

| Sodium | 29% to 49% | For natural sodium in crops, you’d need nearly 2 carrots to match the mineral content of 1 carrot from the past. |

| Calcium | 16% to 46% | If you’re eating broccoli for calcium, you might need nearly double (1.8x) the amount to hit the same levels. |

| Iron | 24% to 27% | 4 bowls of spinach to equal the iron in 3 bowls from 50 years ago. |

| Magnesium | 16% to 24% | You now need about 1.25 servings of magnesium-rich greens to equal 1 serving from the 1950s. |

| Potassium | 16% to 19% | You’d need to eat roughly 6 bananas today to get the potassium that 5 bananas used to provide. |

[Data from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10969708/#sec2-foods-13-00877 ]

Food in India was once medicine. For a Vishwaguru aspiring to lead the world, it is ironic that we are caught in a cycle of an unsustainable farming system, and that we resist reassessing a farming system that is exhausting soil, water, air, and human health. Hybrid seed technology is not inherently bad, but it is unsustainable when applied blindly.