As India prepares for the next round of negotiations for the proposed free trade agreement (FTA) with the EU, scheduled for September 23-27 this year, discussions are set to intensify around critical sustainability measures. Among these, the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) and the EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR) are expected to be at the forefront of the dialogue with the 27-nation bloc. These measures reflect the EU’s commitment to integrating sustainability into its trade policy, a stance that could have significant implications for India.

The CBAM, in particular, represents a transformative approach by the EU designed to prevent carbon leakage and promote environmental accountability by imposing a carbon price on imports of specific goods entering the EU. This carbon price will mirror the cost paid by EU producers under the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS), ensuring that products from outside the EU do not gain an unfair advantage due to lower environmental standards in their countries of origin. The mechanism is initially focused on carbon-intensive sectors such as steel, cement, aluminium, fertilisers, and electricity, with the possibility of expanding to other industries over time.

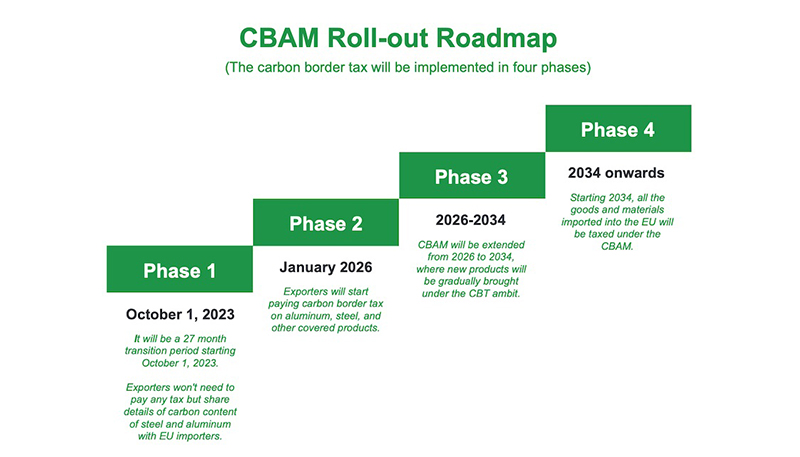

The rollout of CBAM is planned to occur in four distinct phases, as illustrated in the following figure:

(Source: India Briefing – https://www.india-briefing.com/news/eu-carbon-border-adjustment-mechanism-impact-india-business-exports-27901.html/ )

For India, in 2022, 27% of its exports of iron, steel, and aluminium products—worth USD 8.2 billion—went to the EU. Additionally, in the year 2021-22, India’s total export of agriculture and allied commodities to the EU amounted to USD 1,725.34 million. The highest exports within this category were coffee, valued at USD $393.96 million, followed by oil cake at USD $208.93 million, rice at USD $121.24 million, tea at USD $106.33 million, and tobacco at USD $164.8 million. The introduction of CBAM is likely to have significant implications for these sectors, raising concerns within India that this mechanism could act as a trade barrier, disproportionately affecting developing countries.

With such a significant portion of exports going to the EU, Indian conglomerates, especially in energy-intensive sectors, stand to see their earnings disrupted as CBAM imposes higher costs. This could severely impact their competitiveness in the EU market, which has long been an important destination for these exports. Meanwhile, the EU’s income from these taxes is expected to surge, benefiting from the substantial value of imports from India.

The potential economic impact of CBAM on India is considerable. As Indian exporters face increased costs due to the carbon pricing imposed by CBAM, their ability to compete in the EU market could be undermined. This could lead to a shift in global trade dynamics as companies seek to source goods from regions with lower carbon-related expenses.

Historical trends have also shown that carbon-intensive production has gradually shifted from developed countries to developing ones, creating disparities in emissions. As Avantika Goswami, who leads the climate change programme at the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE), pointed out in the Deccan Herald, today’s differences in emissions intensity are also rooted in the historical context, where the Global North heavily relied on fossil fuels like coal during the Industrial Revolution to amass wealth and build strong economies. The imposition of CBAM overlooks this, unfairly penalising countries in the Global South. From a different perspective, imposing a cost on the Global North for cheap polluting energy use, offshoring practices, and reliance on inexpensive offsets could be seen as a necessary course correction, rather than retaliation, to address these long-standing inequities.

India’s readiness for CBAM is currently a mixed picture. The nation has made strides in renewable energy, with ambitious targets for expanding solar and wind power. Policy measures to enhance energy efficiency and reduce emissions have also been introduced. However, the industrial sector remains deeply intertwined with coal, and the shift to cleaner technologies is still in the early stages. To effectively navigate the challenges posed by CBAM, India will need to bolster its domestic carbon pricing mechanisms and rapidly scale up the deployment of clean energy technologies. This may include increasing investments in renewables, enhancing industrial energy efficiency, and promoting the adoption of green hydrogen.

Additionally, India will need to engage diplomatically with the EU to mitigate the potential trade impacts of CBAM. Negotiating exemptions or favourable terms for developing countries could be a part of this strategy. Ensuring that CBAM does not unduly burden Indian industries while supporting the country’s broader green transition will be a delicate balancing act.

Looking ahead, CBAM presents both risks and opportunities for India. While the mechanism could pose significant challenges to the country’s export competitiveness and economic stability, it also offers a chance to align with global sustainability standards. The upcoming FTA talks with the EU will be a critical juncture, shaping the trajectory of India’s response to CBAM and its broader role in addressing global climate challenges.