India feeds itself on nitrogen. Unfortunately, that is not a metaphor. It is an intentionally created budget line, a supply chain, and a deeply entrenched policy choice. Every year, Indian farms consume over 20 million tonnes of nitrogen, primarily in the form of urea. That single nutrient now accounts for nearly two-thirds of all nutrients applied to crops. No other major agricultural economy leans this heavily on one input.

For decades, this dependence has been celebrated as a success story. Cheap urea helped India avoid famines, stabilise yields, and achieve food security. But what began as a life-saving intervention has quietly evolved into a structural addiction—one that is now degrading soils, contaminating water, inflating public spending, and creating risks that India’s farm economy is poorly equipped to handle.

Why do Indian farms use so much nitrogen?

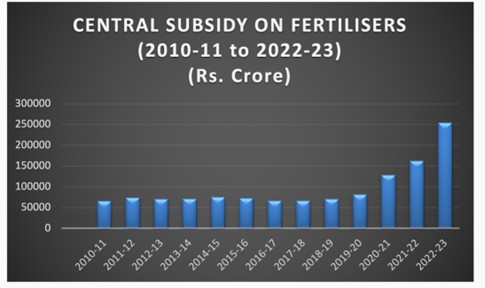

The answer is not agronomy, but the price. A 45-kg bag of urea costs between ₹2,000 and ₹2,450 to produce, import, and deliver. Yet farmers across India buy the same bag for about ₹266. The gap is paid for by the government. In 2024–25 alone, India’s fertiliser subsidy bill was revised to ₹1.91 lakh crore.

This single policy choice shapes farmer behaviour more powerfully than any training programme ever could. When nitrogen is cheap and everything else is not, farmers use more nitrogen. Not out of ignorance, but because the system rewards it.

Over time, this distortion has warped India’s nutrient balance. Agronomists recommend an NPK ratio (Nitrogen/Phosphorus/Potassium Ratio) of 4:2:1, a balance that keeps soils productive. Today, India operates at 9.8:3.7:1. Nitrogen does the heavy lifting. Phosphorus and potassium are left struggling to keep up.

Think of it as a dietary problem. Nitrogen is like fast food: cheap, filling, and immediately satisfying. Phosphorus and potassium are essential nutrients, but often skipped when budgets are tight.

When more fertiliser stops working

For years, adding more urea delivered visible results. Yields rose. Green Revolution crops responded well. But soils, unlike spreadsheets, remember history.

Excess nitrogen acidifies soil. It lowers pH, washes away essential nutrients, and releases aluminium in forms that damage plant roots. Eventually, crops cease responding as they once did. Farmers apply more fertiliser each year to compensate, but yields nevertheless stagnate.

This is now a familiar complaint in high-input belts like Punjab: “Earlier, four bags were enough. Now, even six or seven don’t help.” Farmers are not confused about the numbers. They are observing the system’s limits manifest. And if this sounds familiar, it should; this is exactly how addiction works.

Year by year, nitrogen consumption on Indian farms increases, enabled by government subsidies. But the long-term cost for this habit is enormous. Research estimates that soil acidification could lead to the loss of 3.3 billion tonnes of soil carbon in India. Carbon is not merely a climate metric. It gives soil its structure, water-holding capacity, and resilience. Lose it, and productivity, the very thing India is chasing through heavy inputs, becomes increasingly expensive to sustain.

Where does all the nitrogen go?

Crops and soil can only absorb so much of the chemical being fed to it at a time. So what crops do not absorb, water carries away. The excess nitrogen leaches into groundwater as nitrate, especially in irrigated and alluvial regions. As India depends heavily on groundwater for both drinking and farming, this turns into a slow-moving but deeply serious crisis, because the health risks associated with nitrate pollution in water are very real.

By 2023, nearly 56% of India’s districts reported excessive nitrate levels in groundwater. The number of affected districts rose from 359 in 2017 to 440 in 2023, with around 20% of water samples exceeding the safe limit of 45 mg/l, set by both the World Health Organisation and the Bureau of Indian Standards. In the last two years, the number would have likely increased.

High nitrate intake is linked to blue baby syndrome, digestive disorders, and increased cancer risk. One risk assessment found that nearly half the children tested in nitrate-affected areas faced non-carcinogenic health risks.

So, fertiliser subsidies, as it turns out, do not end at the farm gate. They travel quietly into aquifers, kitchens, and eventually, the public health system.

The climate contradiction hiding in plain sight

Nitrogen overuse has another cost that rarely comes up in climate discussions.

Agriculture accounts for over 80% of India’s nitrous oxide emissions. Nitrous oxide is a greenhouse gas nearly 300 times more potent than carbon dioxide, and its primary source is the breakdown of synthetic nitrogen fertilisers in soil.

Since the 1960s, India’s nitrous oxide emissions have increased roughly fourfold, tracking fertiliser use rather than population growth. The implication is uncomfortable but unavoidable: India cannot meet its climate goals without addressing how it fertilises its crops.

Fixes that helped with fertiliser overuse, but not enough

It’s not like nitrogen is not important for our soil, so what can we do?

Improving Nutrient Use Efficiency (NUE), which involves ensuring that a greater proportion of applied nitrogen is utilized by the crop rather than lost to the environment, is considered as one of the solutions. It is referred to as the most immediate and critical strategy for mitigating the impacts of chemical nitrogen use. And the Indian government has tried their hands at it with Neem-coated urea.

Made mandatory in 2015, neem-coated urea successfully curtailed industrial diversion and saved an estimated ₹10,000 crore. As a fiscal reform, it worked. But as an agronomic solution, its impact has been limited.

Neem coating slows nitrogen release, but its benefits are uneven, stronger in irrigated systems and weaker in rain-fed ones. Since over half of India’s cropped area is rain-fed, a large share of urea continues to deliver minimal efficiency gains.

Precision tools like nitrogen sensors and fertigation systems offer a better solution. Field data shows nitrogen savings of around 10% per hectare, along with sharp reductions in nitrate leaching. But these technologies require capital, training, and infrastructure—precisely where public investment has been weakest.

While NUE helps dealing with this problem, it does not fix a system that actively encourages overuse.

The alternatives to nitrogenous fertilisers that India ignores

India does not lack nitrogen alternatives. Biofertilisers, green manuring, and biological nitrogen fixation are proven technologies. Legume-based green manures can supply 50–175 kg of nitrogen per hectare. Biofertilisers can reduce input costs by 40–50% per acre and deliver higher net profits over time.

Even simple changes, such as applying biofertilisers and small amounts of nitrogen during tilling, instead of skipping them, can significantly reduce total nitrogen use. Yet only 1.5% of India’s farmland uses these systems at scale.

For every $1,000 India spends on sustainable agriculture, it spends roughly $100,000 subsidising chemical fertilisers. This imbalance makes biological inputs appear expensive and uncertain, especially to small farmers who cannot afford even one failed season. As a result, less than 5% of farmers account for 95% of biofertiliser usage nationally.

At this point, I’d like you to take a pause and think – for farmers who struggle to earn enough to sustain themselves, would it not be more effective to ensure that subsidised food actually reaches them, rather than leaking to local power brokers and better-off households? Food security would reduce anxiety around survival and create space to experiment with alternatives that improve soil health. Transition support like training, biofertiliser subsidies, and compensation for initial crop failures would cost far less than continuing the current cycle.

What other countries have already learned about fertilisers’ role in agriculture?

China faced a similar problem: heavy fertiliser use, rising environmental damage, and falling efficiency. In 2015, it changed course. By rationalising subsidies and promoting precision technologies, China reduced chemical fertiliser use by over 12% in just four years, without compromising food output.

Europe is moving further. Under the Farm to Fork strategy, the EU aims to cut fertiliser use by 20% by 2030, embedding nitrogen limits into environmental law.

The Netherlands shows the cost of delay. Court-mandated nitrogen caps eventually forced €1.47 billion in farm buyouts, a far more expensive solution than gradual reform.

The nitrogen reforms India keeps postponing

Standing on the edge of ecological and fiscal stress, India can no longer afford to postpone nitrogen reform. As long as urea remains dramatically underpriced, nitrogen overuse will persist—regardless of advisories or awareness campaigns. Reform does not mean abandoning farmers. It means shifting support from blanket subsidies to performance-linked incentives, precision tools, quality-controlled bio-inputs, and insurance mechanisms that protect farmers during the transition.

Cheap nitrogen once saved India from hunger. Today, it is quietly taxing soils, poisoning water, inflating budgets, and locking farmers into diminishing returns. The question is no longer whether India can afford to fix this system. It is how long it can afford not to.