Spices, the edible, aromatic substances, are the soul of Indian food. Woven deeply into India’s history, culture, and identity, India’s identity with premium spices is under threat. Indian spices are increasingly being rejected in global markets due to serious concerns around their quality and the safety of their production.

Indian Spice Exports Are Facing a Trust Crisis

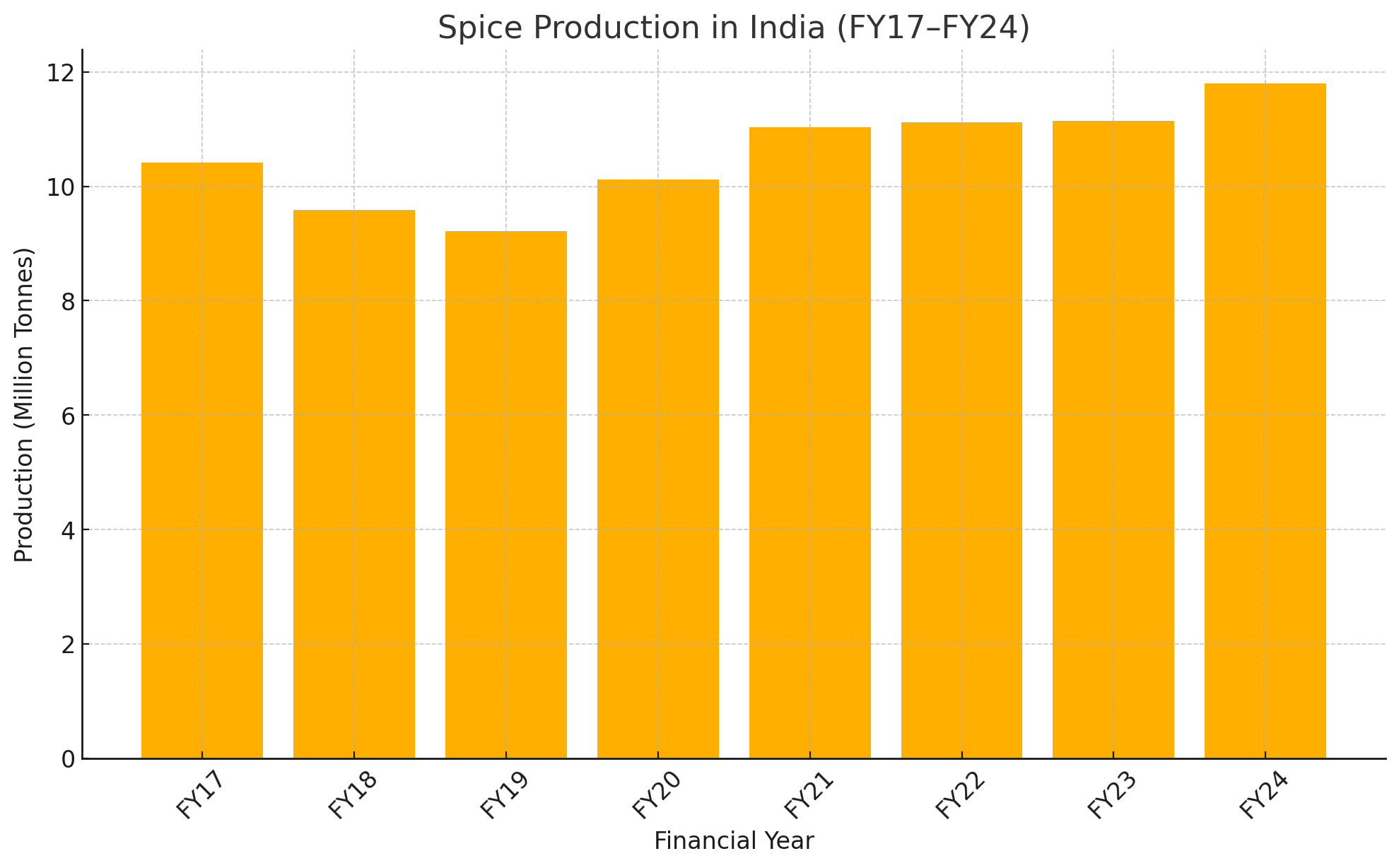

India has long held the distinction of being both the largest producer and exporter of spices in the world. But in the last few years, the number of Indian spice shipments returned from foreign ports due to the presence of carcinogenic substances has risen by nearly 20%. This is reflected in the export earnings too, which declined from USD 4.46 billion in FY24 to USD 3.36 billion in FY25.

This concerning trend puts India’s century-old reputation in jeopardy. If global buyers start turning to smaller, cleaner producers, India could lose both its market share and symbolic leadership in the spice world.

At the same time, there are domestic implications too. If exported spices are being flagged for harmful chemicals, what does that say about the spices being sold and consumed within India? Are our spices really loaded with unsafe chemicals, or are the global standards becoming too difficult to meet?

Why Are Indian Spices Being Rejected?

India currently exports over 225 different spice products to approximately 200 countries. However, major importers like China, the USA, the UAE, and the UK have all flagged and rejected multiple consignments of Indian spices in recent years. Why is this happening?

At the centre of the issue lies the widespread and liberal use of hazardous agrochemicals.

Most Indian spice farms continue to use pesticides based on organophosphates and neonicotinoids—both of which are known to harm humans and the environment. Several of these chemicals have already been banned in the European Union.

Which countries have rejected Indian spices?

Confusion Over Pesticide Residue Limits (MRLs) on Indian Spices

To manage chemical residues, different countries have set Maximum Residue Limits (MRLs), which define how much pesticide residue can remain in a food product. But here’s the catch—these limits vary from country to country, creating confusion and compliance headaches for Indian exporters.

| Pesticide/Chemical | EU MRL/Status | US Tolerance/Status |

| Ethylene Oxide (EtO) | Banned (MRL 0.1 mg/kg as sum of EtO and 2-CE) | Permitted (MRL 7 mg/kg); EPA proposing phased cancellation for spices |

| Chlorpyrifos | 0.01 mg/kg | Tolerances established by EPA; enforced by FDA |

| Nicotine | 0.3 mg/kg (reinstated Feb 2024) | Tolerances established by EPA; enforced by FDA |

| Methyl Parathion | Subject to EU MRLs; likely very low or banned | Tolerances established by EPA; enforced by FDA |

| DDT | Subject to EU MRLs; largely banned | Tolerances established by EPA; enforced by FDA |

| Salmonella | Must be completely absent | FDA requires “validated kill step” to control pathogens |

On the domestic front, the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) hasn’t exactly helped matters. Initially, it had set the MRL for many pesticides at 0.01 mg/kg, but even that was poorly enforced. In 2024, FSSAI controversially raised the limit to 0.1 mg/kg—a move reportedly influenced by a Central Insecticides Board and Registration Committee (CIB&RC) report.

Even more worrying is that FSSAI has set the MRL at 0.1 mg/kg for certain unregistered pesticides, effectively allowing chemicals that haven’t been formally approved for use in agriculture.

MRLs typically focus on individual pesticides, but experts argue this method misses a crucial point. The Indian spices are dried and concentrated, which means any pesticide residue becomes more potent. When a mix of chemicals is used, the interaction between them can amplify harmful effects. This so-called “cocktail effect” is especially relevant for spices, yet it remains under-researched in India, even as international scrutiny grows.

Lack of Consistent Regulations

Another worry for Indian spice exporters is ethylene oxide, a chemical used to sterilise spices. The US permits (and even promotes) its use to eliminate bacteria like Salmonella, but countries like China, Europe, and the UAE have rejected Indian shipments for containing excessive levels of it. Ethylene oxide is believed to be a carcinogen and may cause nerve damage if consumed in high quantities. This puts Indian exporters in a bind.

For a country like India that is actively building global trade relationships, this regulatory contradiction makes it critical to develop a streamlined, harmonised export policy. Without that, national and state agencies have little clarity on what to advise or regulate.

Why Indian Exporters Are Turning to Southeast Asia

These conflicting international standards could explain why many Indian exporters are now looking towards Southeast Asia. These markets are perceived as more flexible and continue to show rising demand for Indian spices.

But there may be another reason: the European Union’s upcoming Green Deal. Though not yet fully implemented for spices, it is expected to bring stricter environmental and residue norms in the near future. Rather than preparing for these changes, the industry appears to be avoiding them altogether by pivoting to less demanding markets.

Is Chemical-less Spice Farming Possible?

However difficult it may be, India can take notes from sustainable agricultural practises in spice production from some of its own states. Uttarakhand, for instance, while contributing modestly to national spice output, follows an all-natural process for crops like turmeric, garlic, chilli, and coriander. These are grown without synthetic inputs and align more closely with the expectations of global markets looking for traceability and sustainability.

The move towards sustainable agriculture might as well be an opportunity for India to reevaluate its farming systems. If institutions like FSSAI were to align better with export standards and actively train farmers in Integrated Pest Management (IPM), India could not only retain its position in global spice markets but lead the next era of safe, clean spice exports.