India and Europe may have resumed trade talks, but that alone won’t be enough to rescue one of India’s most iconic exports—Assam tea—if the country doesn’t first focus on fixing its collapsing farming system.

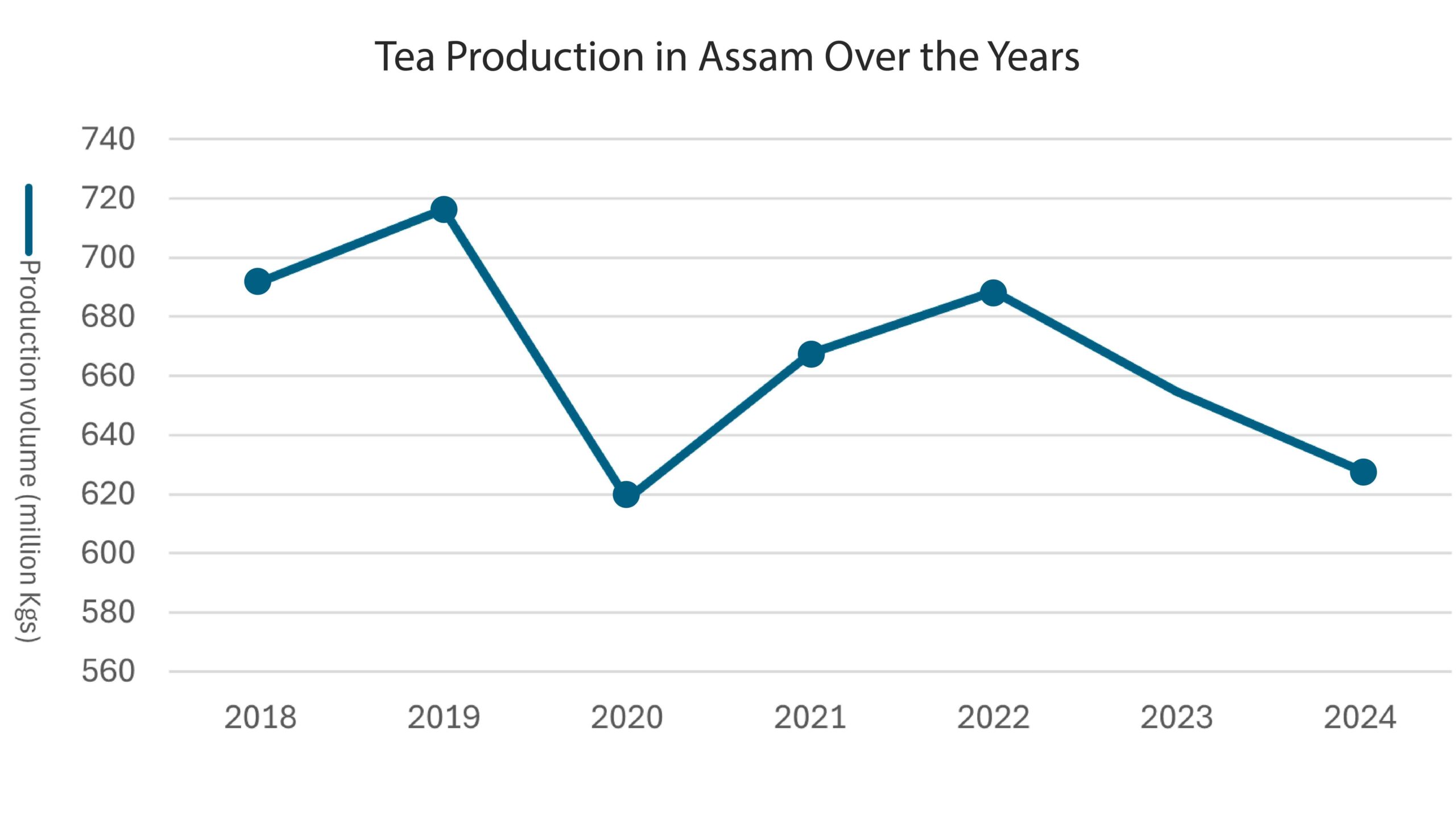

India is not just a large consumer of tea; it has long been a significant exporter as well. The country’s climate and soil have historically produced punchy, robust teas—so much so that tea cultivation was one of the early reasons for over 200 years-long British colonisation. Among India’s tea-producing regions, Assam carries the heaviest burden, accounting for 52% of the total national output. Unsurprisingly, it also plays a central role in India’s tea exports, which clocked in $900 million in FY 2024–25. Yet, Assam’s share in these exports is shrinking—even though its black tea remains internationally popular. North India’s share in India’s total tea export reduced from over 80% to approximately 60% between 2020 and 2024.

Why is this happening?

A major reason is the European Union’s evolving standards for food-grade imports. First came the Maximum Residue Level (MRL) regulations, and later many international and domestic buyers rejected several consignments of Indian tea because of the presence of pesticides and chemicals beyond permissible limits.

| Term in Brief: MRLs Maximum Residue Levels are the highest permissible levels of pesticide residues allowed in food and agricultural products. Set by importing countries to ensure food safety, MRLs vary globally — often with EU standards being far stricter than India’s. |

Now, the EU’s Green Deal is at the doorstep, bringing with it an even more comprehensive set of sustainability benchmarks that Indian exporters must meet to retain access to European markets. While Russia and Iran remain top importers of Indian tea, these regulations could still depress global market prices for Assam tea—especially as African black tea, grown under more sustainable conditions, floods the market.

| Term in Brief: EU Green Deal The EU Green Deal is a comprehensive strategy aimed at combating climate change, preserving biodiversity, reducing pollution, and promoting a sustainable economy. Under it, importers must identify and mitigate environmental risks throughout the supply chain — from “farm to fork” — including pesticide use, deforestation, and labour conditions. |

In India, regions like Coonoor in Tamil Nadu are also drawing international buyers with their eco-friendly methods. The trouble is, Assam’s delicate ecosystem and climate aren’t as adaptable as that of Africa or southern India. Rapid transitions to EU-compliant agricultural systems are not only difficult—they’re nearly impossible in the short term.

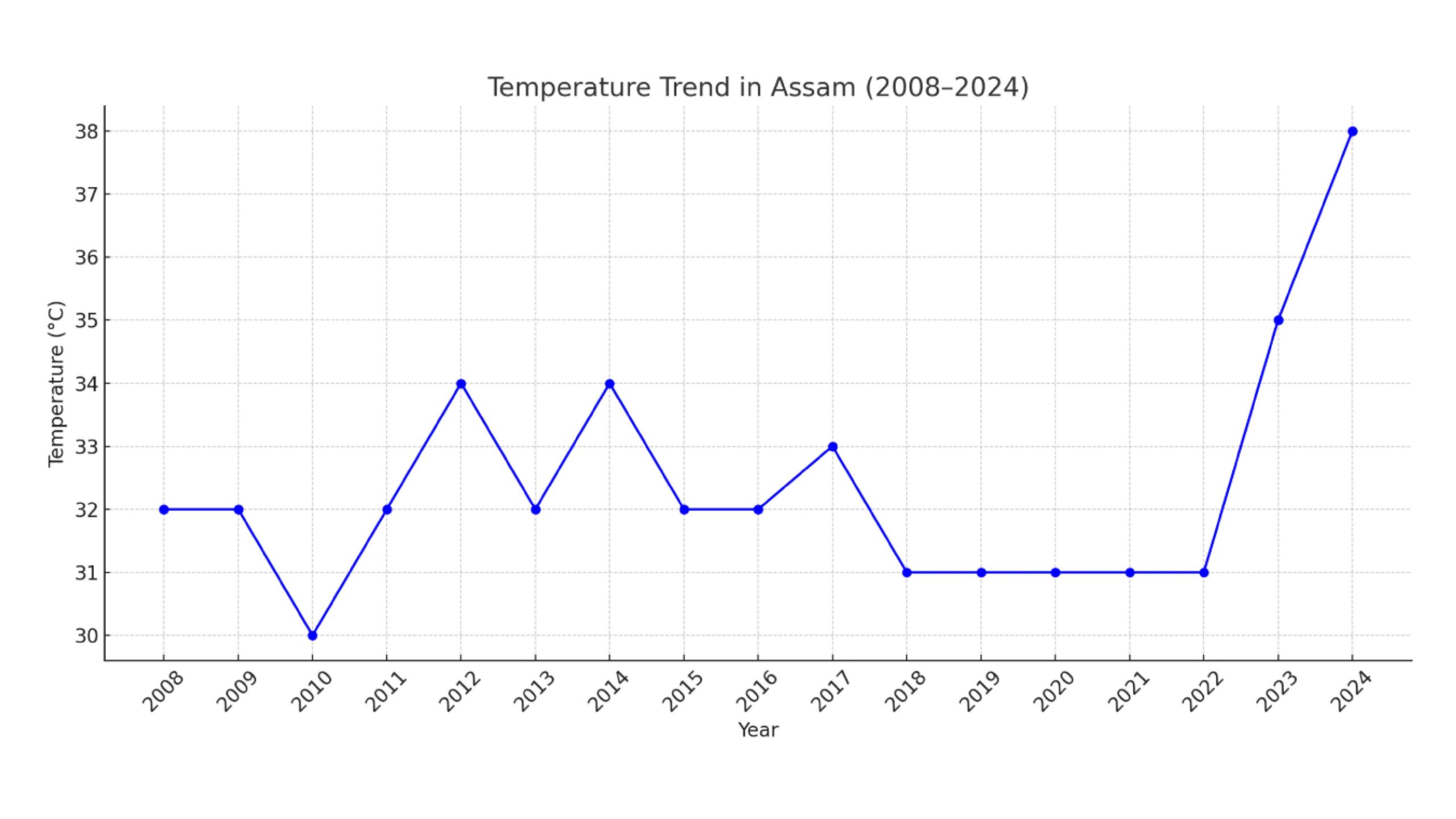

Add to this the impact of climate change. Assam is experiencing erratic rainfall patterns and rising summer temperatures, creating an unpredictable farming environment.

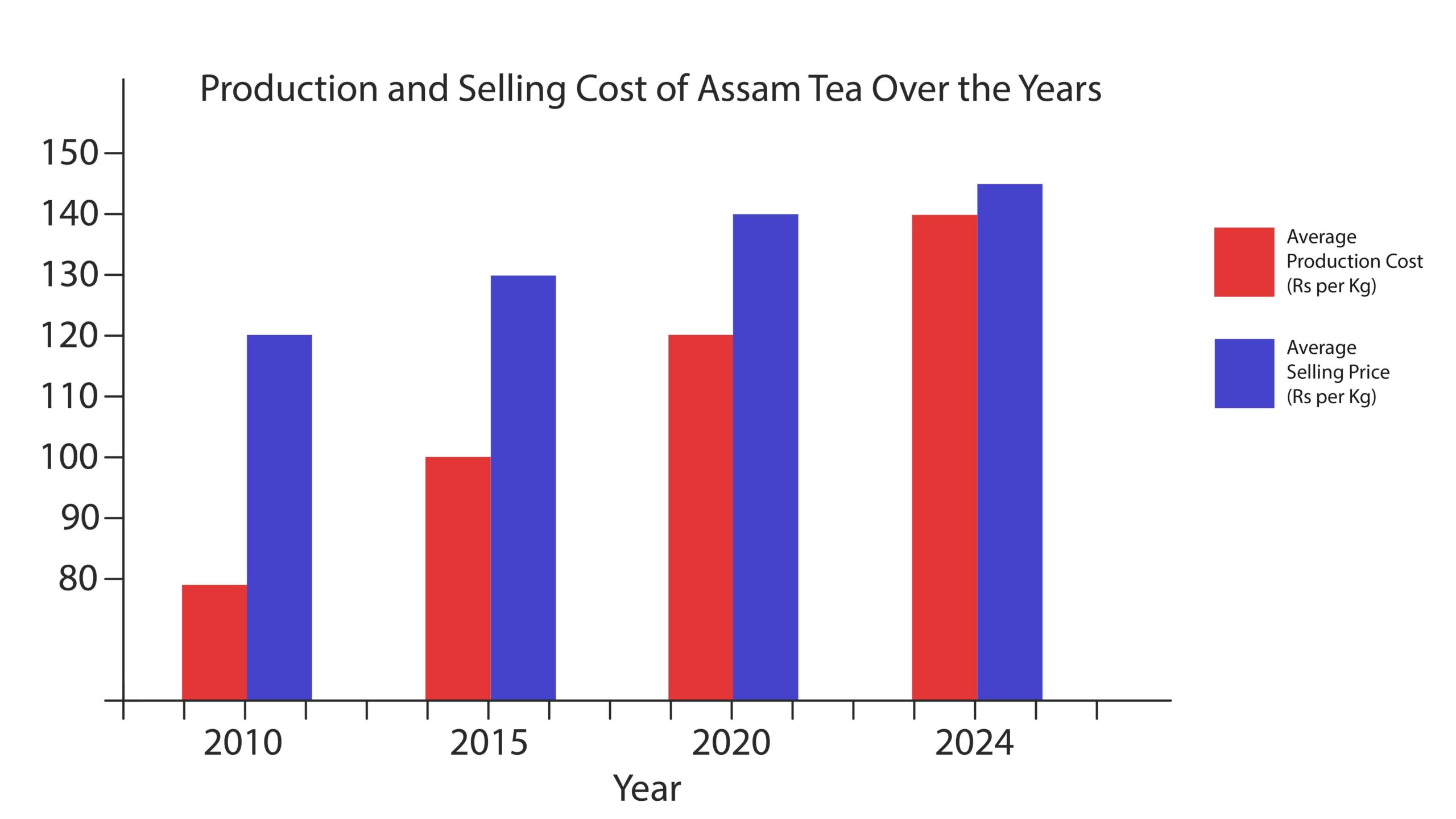

Such fluctuations, combined with high labour costs and poor soil health, have sharply increased production costs in Assam. At the same time, tea yields are dropping, and the selling price hasn’t kept up.

So What Can Be Done?

According to Dr. Chandrasekhara Biradar, Country Director (India) at CIFOR, decades of conventional farming with chemical pesticides and fertilisers have left Assam’s soil depleted. Transitioning to sustainable farming could take at least 3–4 years—and in that time, many farms may yield little or no output. That’s a financial death sentence for the region’s small farmers, most of whom rely on hand-to-mouth incomes. Yet, delaying the transition only widens the recovery gap.

Dr. Biradar emphasizes that adopting sustainable practices will ultimately help make crops more resilient to climate change. But again, this is easier said than done.

Take the Tea Mosquito Bug, for instance—a pest that can cause catastrophic losses, ranging from 50% to a complete wipeout of the tea harvest. The commonly used solution: neonicotinoid-derived pesticides. However, to protect bees and biodiversity, the EU has capped permissible residue levels of pesticides like Thiacloprid at 0.05 ppm from May 2025. Assam’s current levels stand at 0.5 ppm—a tenfold difference. And, alternatives like Integrated Pest Management (IPM), which involves introducing predatory insects, have shown limited success so far.

Regions like South India and Africa don’t struggle with the same pest pressures, giving them an edge. As international markets increasingly prefer organic teas from these regions, Assam’s economy—once synonymous with Indian tea—is under threat.

The bigger risk? If global consumers develop a taste for Kenyan black tea, Assam may lose its centuries-old market prestige altogether.

Farmers alone cannot shoulder this burden. Most lack the knowledge, tools, and financial resources to make this shift. Government bodies, research institutes, and global agencies must step in—not just with policy papers, but with real, on-ground solutions. Because if action isn’t taken soon, the story of Assam tea might become one of cultural and economic loss.